All the lenses we use for photography (with a few exotic and very expensive exceptions) are designed and optimized for the visible range. This applies to sharpness, focus and the coating to protect against ghost images in backlighting - the most well-known problem is probably the infrared hotspot. Nevertheless, excellent results can still be achieved with most lenses in the IR range. Unfortunately, very few of these faults can be seen in a lens before it has been tested. However, some problems are common to many lenses, so let's take a look at how we can work around them.

Loss of sharpness and detail

The optical design of our lenses is calculated for the visible range. In principle, a certain loss of sharpness can be measured with every lens when it is used for infrared photography. With most lenses, this is so small that there is hardly any need to talk about it. Much worse is often the loss of sharpness towards the edge of the image - this occurs particularly with wide-angle and ultra-wide-angle lenses. To improve sharpness in general, it is helpful to close the aperture, as in "normal" photography. However, this leads to other problems. On the one hand, stopping down can cause a hotspot, and on the other hand, long-wave infrared light is much more likely to be affected by diffraction blurring than the visible range. In general, the aperture should only be closed as far as absolutely necessary for IR images.

Autofocus in Infrared Photography

Correctly functioning autofocus can be more critical than image sharpness. With modern mirrorless cameras, there are usually no problems or surprises here. But with digital SLR cameras, you have to pay attention to a few things.

To take a picture in the infrared range, you need to focus "a little closer" than in the visible spectrum. On old manual lenses, a red IR mark was often attached to the focus ring for this purpose. In the AF age, focusing is no longer the task of the photographer but of the camera - and this should also be the case in digital infrared photography. In a professional infrared conversion, the autofocus of the SLR camera is adjusted once, so that the camera's AF will from now on focus all lenses correctly for the IR range. A complete infrared conversion is the only way to be able to use the autofocus on a DSLR and therefore to focus quickly and reliably.

A peculiarity of older lenses is often the occurrence of backfocus when using a DSLR. The difference between visible and IR light, which is compensated for on the camera by the focus adjustment, is not constant for all lenses. It depends on the optical construction of the respective lens (mainly on the quality of the aspherical correction) and possibly the set focal length (for zoom lenses). With most modern autofocus lenses, there should be no problems with autofocus. The older a lens is, the more likely it is that it is a poorly or not at all aspherically corrected design. However, there is no rule here; unfortunately, only trial and error will help.

Unfortunately, I cannot promise perfect focus for every lens when using a DSLR. In order to achieve consistently perfect results even with "problem lenses", it makes the most sense to use a (DSLR) camera with contrast autofocus via the sensor. The focus difference is not a problem with contrast AF via the sensor, as it already sees the IR light and focuses accurately. With mirrorless system cameras, the focus position is generally unproblematic, as these cameras work permanently in "LiveView mode" due to their design.

Infrared Hotspot and countermeasures

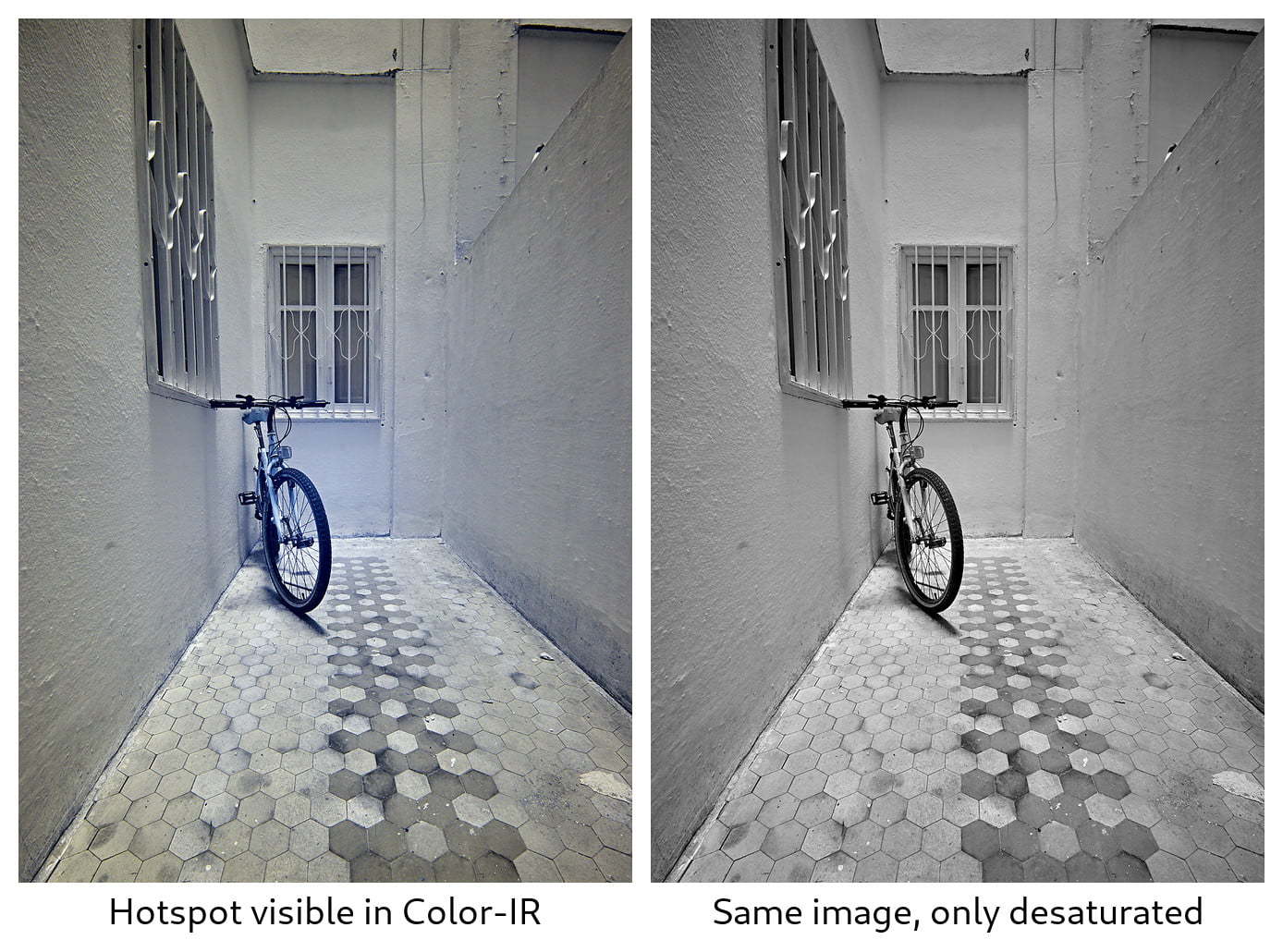

A very unpleasant image flaw is the hotspot. A hotspot is a circular area in the center of the image that is brighter and therefore stands out clearly. Often the blue channel of the image is more affected by this, which is why a hotspot appears as a color blob to make it even worse.

The hotspot is due to the inadequate coating of the lenses in the IR range, which means that it is not easy to avoid it. If a lens is affected, it can help to experiment with different apertures. The intensity of the hotspot increases when stopping down, which is another reason not to stop down the lenses too far. In addition, backlighting situations can intensify the hotspot - the use of a lens hood should therefore be mandatory at least for the affected lenses.

Once a hotspot is in the picture, you can try to retouch it out on the PC. Even if this seems possible, it is often tedious and time-consuming work. A very quick and effective technique is to convert the image to black and white. The hotspot occurs mainly in color IRs, in a monochrome image it is only very faint or not at all.

Lens flares and backlight

In backlight, the global image contrast of an IR image drops very quickly. Shadow areas become dull and muddy, even hotspots can be promoted. Besides the simple rule of not taking pictures in backlit situations, the first means of choice is to shade the front lens with care. This can be done with a hand or by putting on a sun shade.

Finally, due to the ineffective coating of most lenses in the IR range, lens flares occur very quickly in backlight situations. This phenomenon can be avoided or at least mitigated by avoiding backlight situations, by using a lens hood and possibly by stopping down. Another option is to creatively incorporate lens flares into the image composition! There are extra filters in many graphics editing programs that artificially create such an effect. We have integrated it right away.

Image problem prediction

Unfortunately, it is not possible to tell in advance whether a lens will produce image errors and, if so, which ones. You can either try it out yourself (remember the 14-day exchange right when buying a lens, used lenses can usually be resold without loss of value), or research the experiences of other photographers with the lens before buying it. There are also a few databases on the Internet that have summarized many user experiences - here you at least have an indication of which lenses might be suitable before you buy them.